A Satanic Indictment

August 24, 2022

When autocratic institutions rise up and steal power straight from the hands of the people, there will always be those with the tenacity to oppose them with their fists to the sky and their hearts looking to a greater future. Such is the indomitable human spirit. For if we are not actively seeking to forge a better path of liberty and prosperity for our children, the very crux of our purpose as humans is irretrievably lost to an ever-stirring sea of oppression.

For every Matrix there must be a Morpheus. For the lost there shall always be a Jesus; a Prophet Muhammad; an Andrew Tate (joking don’t sue me). But what happens when the hope placed in the ever-dependable communities and long revered institutions of our society proves to be erroneously placed?

Maybe if we need a Prophet in the 21st century, the only purpose they’ll serve will be to liberate our society from the archaic influence of previous Prophets.

For millennia, churches were places of spiritual nourishment and enlightenment. Places of ornate beauty to mirror the beauty of another realm in this one. Yet according to the ABC, the Catholic Church enabled and concealed over 200,000 cases of sexual abuse of children by clergy since 1950 in France alone. So, when the fortresses of a holy God, built to stand against the forces of evil on the Earth, disgrace society and betray the trust of humanity, how should we oppose such powerful institutions?

Perhaps the best tool to disarm the faculties of repression and proliferation of harmful ideologies and institutions is art. As a species, we’ve been making it for millennia, and it seems to strike the balance between exposing underrepresented truths while entertaining and engaging the mind.

Somehow, despite the abject trauma of HSC English, I cannot help but think that more specifically, literature is in fact one of the best tools to oppose evil ideologies. It seems the William Clarke English faculty may be correct…

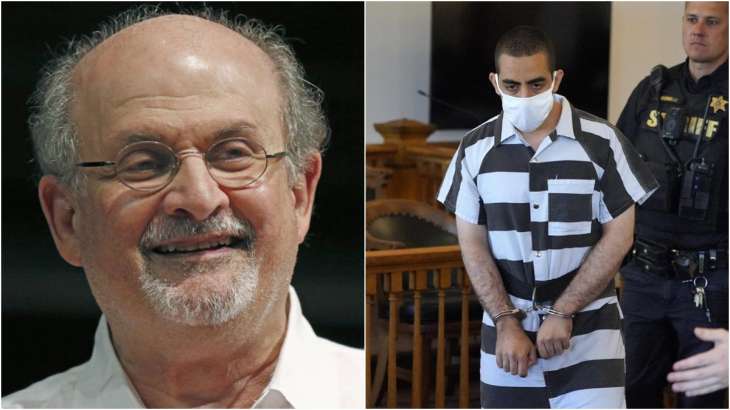

British-American novelist Salman Rushdie published his highly controversial, satirical critique of the Quran and extremist Islam, The Satanic Verses, in 1988, incorporating aspects of the disorientation and alienation of the immigrant experience and the conformity encouraged by oppressive religious ideologies. He was consequently met with severe backlash, including numerous death threats, from the supranational Muslim Ummah (community), as his criticisms were equated to blasphemy, which is punishable by death under Sharia Law.

The novelist was placed under sentence of death by the Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa (a ruling on a point of Islamic law given by a recognized authority) in 1989 and has been effectively living in hiding since then. A bounty of US$3 million was also linked to the fatwa. Such is the danger of speaking out against certain ideologies and the immense courage of Rushdie in doing so through his highly controversial novel.

Since then, the murderous frenzy aroused by his novel had seemed to all but dissipate with time, with Rushdie himself declaring in July: “nowadays my life is very normal again”, a mere fortnight before he was brutally stabbed ten times by a radical Islamist at a speaking engagement in New York two weeks ago.

The suspect was identified as 24-year-old Lebanese-American Hadi Matar, a radicalised youth who, according to The Independent, had seemed withdrawn and isolated to his mother since a trip to the Middle East in 2018.

That the very evil of the ideology critiqued by Rushdie has returned to bite him back 33 years later is a cruel indication of the potential for youth radicalisation within certain violent ultra-fundamentalist sects of Islam. Despite the novelist’s efforts to oppose the propagation of extremist Islam through his literature, this dogma has managed to seed itself in the next generation, with no sign of stopping any time soon.

Ironically, Rushdie was about to give a talk hailing the United States as a safe haven for exiled writers and had pledged to tour the country to create new opportunities for the asylum and protection of persecuted artists prior to going on stage.

Following the attempted assassination, as Rushdie’s condition stabilised in hospital, his son Zafar stated: “Free speech is the whole thing, the whole ball game. Free speech is life itself.”

Severely injured and likely to lose his right eye, the attack on Rushdie represents a blatant attack on free speech and democracy, illustrating to the international community the sheer and alarming potential of extremist ideologies to poison the well of public discourse and unrestricted thought.

The risk of extreme harm (even the loss of an eye) and/or death which is faced by any opponent of extremist doctrine is a necessary one that must, unfortunately, be taken for the sake of truth and to prevent the proliferation of evil belief systems.

We must openly defend the foundational precepts upon which our civilisation is built, or else risk the loss of everything we stand for because we were too afraid to oppose harmful ideologies. There is no room for political correctness in the ideological battle for the future of humanity.

For our world to flourish in the trust of the various institutions across all facets of society, we must have a platform to actively and unimpededly oppose any potential injustice or malice being perpetrated by institutions, religious or otherwise, either openly or in secret.

For every tyrannical, theocratic religious ideology, there must be a Salman Rushdie.